By Terence Ho | Foundation of HKPLTW

Terence is a Research Coordinator for the Foundation of HKPLTW with interests in history & traditions, social organization & inter-group relations, culture & religion, and economics & politics of Canadian Indigenous People and Visible Minorities. Follow him on Twitter: @hkpltw

Terence is a Research Coordinator for the Foundation of HKPLTW with interests in history & traditions, social organization & inter-group relations, culture & religion, and economics & politics of Canadian Indigenous People and Visible Minorities. Follow him on Twitter: @hkpltw

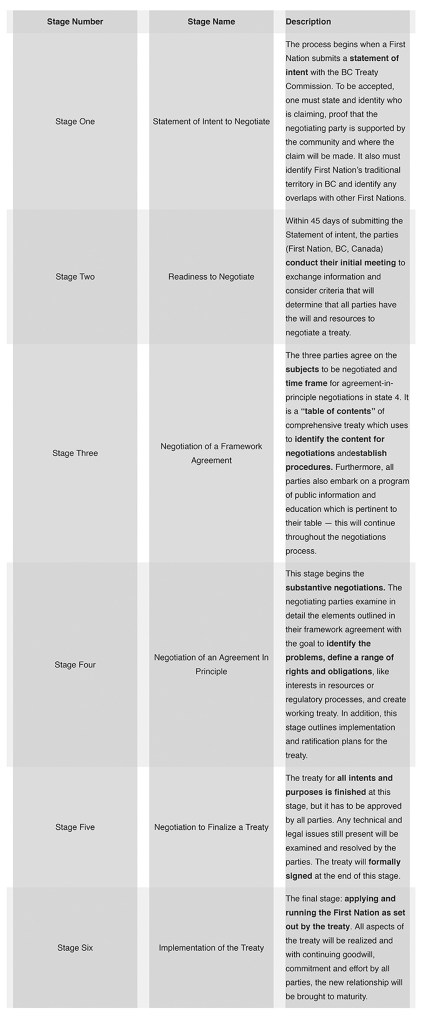

British Columbia Treaty Process (BCTP) is the modern negotiation process in B.C. Its main goal is to resolve outstanding land claims issues and reach a partial agreement with First Nations over the title in the 90s. In the last article, I explain the six stages of the process. In this article, I will expand and explain why the B.C. treaty process is controversial and why it is not entirely successful at settling issues of Aboriginal title.

Differences in the Understandings of Aboriginal Title

I believe B.C. Treaty Process is a necessary first step for both the First Nations and B.C. governments. The process was established in 1991, which provides a guideline for treaty-making that includes a list of 19 principles for negotiations. However, these 19 principles are overly vague, allowing the parties a considerable amount of leeway to how they fashion their participation in the process. Because of this, many treaties falls short. One topic that prevents negotiation from continuing is the differences between the non-Aboriginal and First Nation sides on the “Understanding of Aboriginal Titles.”

The B.C. government’s interpretations of “Aboriginal title” differs from First Nation understandings of title. For the government, the Aboriginal title can be ceded or transferred only to the Crown. Many First Nation communities view the interpretation to be controversial — it favours the B.C. government as it assumes the Crown’s sovereignty without questioning its legitimacy.

Many First Nation activists argue with their definition of ”Aboriginal title.” By defining Aboriginal title using B.C. and Canadian law concepts, they say that the underlying complexities within First Nation understandings of title (based on a reciprocal relationship to the land) are circumscribed. Furthermore, some organizations, such as the UBCIC, argue that the emphasis on legal definitions of Aboriginal title detracts from how title may or may not be recognized and how First Nation communities may assert their title in day-to-day experiences.

As a result, numerous First Nation activist organizations refuse to accept the B.C. government’s definitions of Aboriginal title. They refuse to resolve issues of Aboriginal title using non-First Nations systems like The B.C. Treaty Process.

First Nations: Aboriginal Title Doesn’t Mean Private Property

To most Canadians and our law system, we would define Aboriginal tittle as a “legal ownership of their lands”. However, the First Nations believe that their tittle to their homelands are rooted in a reciprocal relationship to the land. They argue that the Canadian land ownership system is inequitable to Aboriginal tittle, and the Canadian view of Private Property has marginalized First Nation peoples in their own homelands in order for non-Aboriginal interests to profit off First Nation territories. This belief explains why many First Nation groups have dropped out or refused to participate in the B.C. Treaty process, believing that the process tries to extinguish title in favour of government.

Conclusion: A Tough Road Ahead To Settle Issues

The B.C. Treaty Process is full of controversy and uncertainty. Both the non-Aboriginal and First Nation seem to be no common grounds regarding the issue of Aboriginal Title. First Nations believe that outstanding Aboriginal title does not mean that private property will be confiscated. On the other hand, the B.C. government states that land is personal property, meaning that a homeowner would be evicted from one’s home if one does not have legal documents to prove one’s ownership.

As of 2021, the current state of B.C. Treaty Process fails at settling issues of Aboriginal title in B.C. This process is very controversial, and the debates are ongoing. Until there is a way that allows progressive First Nation interests while respecting the Canadian law system — The B.C. Treaty Process will remain controversial and will not be entirely successful at settling issues of Aboriginal title.

Bibliography

McNeil, Kent. “The Meaning of Aboriginal Title.” In Michael Asch, ed. Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equality, and Respect for Difference. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997. 135-154.

Raibmon, Paige, “Unmaking native Space: A genealogy of Indian Policy, Settler Practice, and the Microtechniques of Dispossession” in Alexandra Harmon, ed. The Power of Promises: Rethinking Indian Treaties in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008: 56-85.

Tennant, Paul, Aboriginal People and Politics: The Indian Land Question in British Columbia, 1849-1989 Vancouver: UBC Press, 1990.

Woolford, Andrew. “Negotiating Affirmative Repair: Symbolic Violence in the British Columbia Treaty Process.” Canadian Journal of Sociology, vol. 29, no. 1, 2004, pp. 111.

Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. Stolen Lands, Broken Promises: Researching the Indian Land Question in British Columbia. (2nd ed.) Vancouver: UBCIC, 2005.

This is an opinion article; the views expressed by me. Follow Me on Twitter: @hkpltw And @Terry_Terence97